Fans & Fitna

Years ago, after I memorized the Quran, I was invited to give a talk at a small college. I asked my teacher and be said, “You’re not ready, no!” I was upset and responded, “It’s a small MSA.” Sheikh said, “The fitna is stronger.”

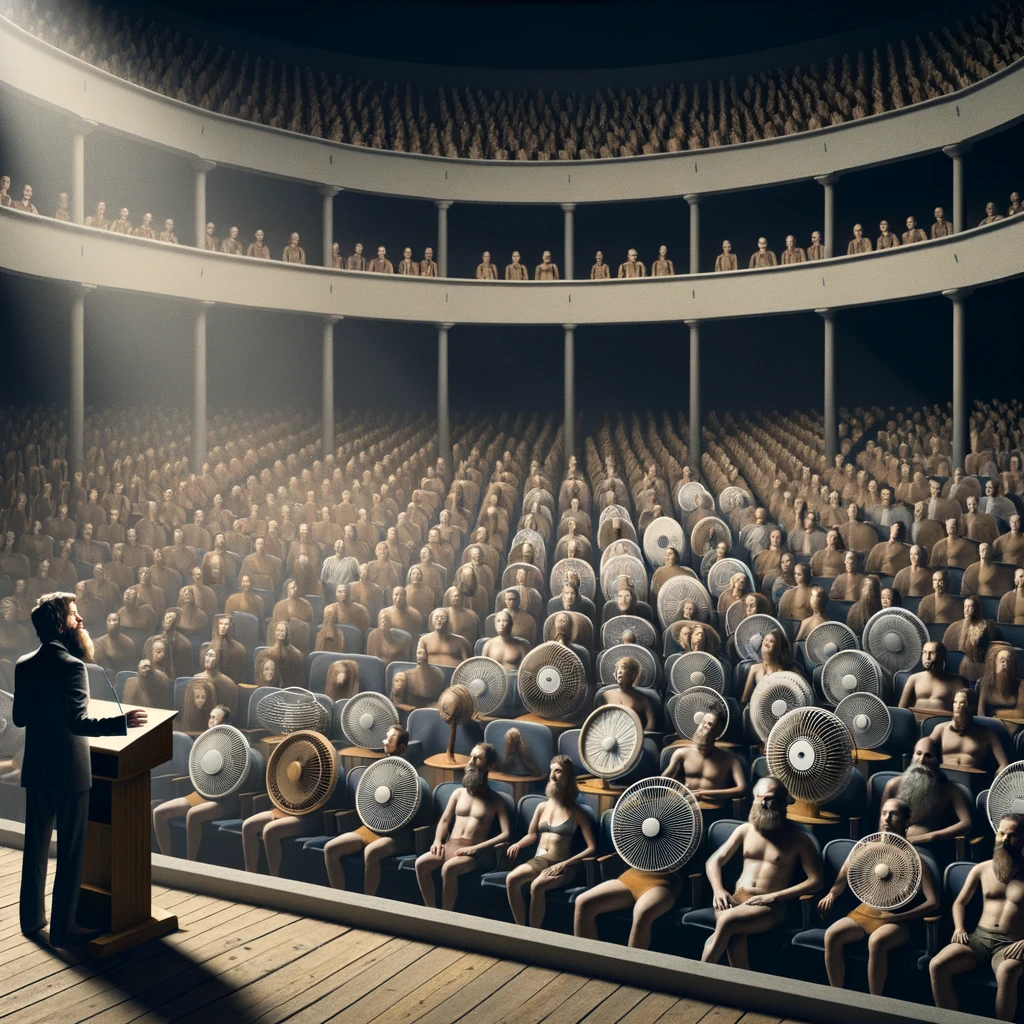

Today, when I see the untrained, charismatic neophyte teaching and reminding Muslims, I worry. I understand that learning religion is not easy; it demands tutelage, hands-on training, and a kind of residency—values that seem lost in this age. But without apprenticeship and time, coupled with scholarship, the caller remains incomplete, embittered, not yet ripe. And with the quick reward of the “religious” pony-show, the investment and time required for learning diminishes.

This is not a novel concern, Dr. Shaban Muhammad Ismail mentions the following incIdents to emphasize the importance of qualifications before teaching.

One day, Sayyiduna Ali, رضي الله عنه, stepped into a mosque and was greeted by the sight of a man energetically preaching, his words casting fear over the congregation. Ali, driven by concern, questioned, “What’s the source of this disturbance?” The response from the crowd was, “He’s urging us on, attempting to remind us.” Sayyiduna, Ali, رضي الله عنه, reapomded, “He is not reminding you of anything except himself.” Imam Ali perceived a deeper reality: this individual was less a guide and more a self-promoter, centering things on himself, not Allah, ‘I am so-and-so, son of so-and-so, take notice of me.’ Recognizing the gap between the man’s quest for recognition and his actual grasp of knowledge, Ali, رضي الله عنه, asked him: “Do you know the difference between the abrogating (nasikh) and the abrogated (mansukh)?” The man’s answer was a simple “No.” In response, Sayyiduna Ali, رضي الله عنه, mandated, “You shall not preach in our mosque.” It was astonishing to Ali, رضي الله عنه, that someone so lacking in fundamental Islamic knowledge was assuming the role of a teacher. The crowd meant nothing. He rebuked the man, stating, “You have doomed yourself and put others in danger.”

Similarly, Sayyidun Ali, رضي الله عنه, passed by a storyteller captivating a large audience. Once again, Ali, رضي الله عنه, inquired if the man could differentiate between the nasikh and mansukh. Receiving another “No,” Sayyiduna Ali, رضي الله عنه, declared, “You have brought ruin upon yourself and your listeners.”

Dr. Shaban Muhammad Ismail, رحمه الله, commenting on these incidents, stressed the essential need for acquiring deep knowledge, particularly in matters of interpretation, before attempting to teach. He cautioned that chasing fame without substantial learning equates to deceit and demonstrates a lack of sincerity. Moreover, he highlighted the critical importance of understanding usul al-fiqh thoroughly, as a foundational prerequisite for anyone aspiring to guide others in religious matters.